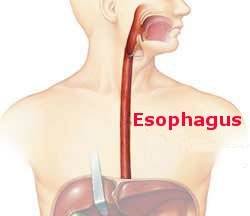

The esophagus is located in the body in a way that complicates surgical access. This tubular organ originates in the neck, passes down into the chest where it lurks behind the heart and is crossed over by the aorta as it courses from right to left when leaving the heart, and terminates below the diaphragm as it merges with the stomach. Translated, the esophagus is in three body cavities and as it passes through the chest is sequestered deep behind the heart.

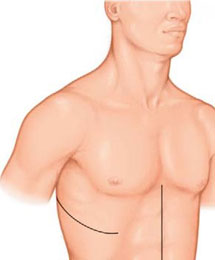

This challenges the surgeon who must decide how to get his or her hands on the target organ as well as choose the best cancer operation once it is exposed and available; but the focus of this blog is the former consideration. Over the years the most commonly used approach both world-wide and in the USA was known by its eponym: the Ivor Lewis esophagectomy, named after the British surgeon who developed it. This operation requires the surgeon to perform a laparotomy to get inside the abdomen to get to the esophagus and stomach. Then a thoracotomy, a second major incision, is necessary to obtain exposure of the esophagus and its lymph nodes in the chest. Some surgeons also added an incision in the neck for good measure. Gathering steam is the practice of using minimally invasive techniques rather than open incisions. Whether the traditional open or the newer minimally invasive strategies, which spare the patient large and painful cuts through muscle, are chosen by the surgeon, this overview illustrates why an esophagectomy takes more time and is more complicated than most operations for cancer in other organs. The impact of two (sometimes three) major incisions also accounts for the challenge to the patient to deal with pain during recovery from the esophagectomy. The issue of choosing the most efficacious and safest cancer operation is yet another layer of complexity for the thoracic surgeon.