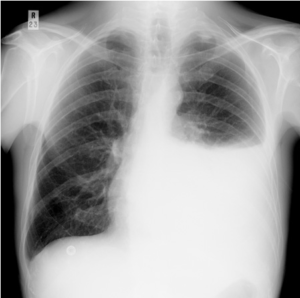

Cancer and fluid in the chest.

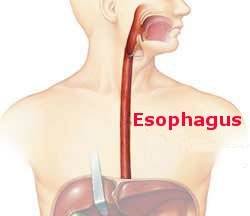

When a surgeon looks into a chest the initial view reveals only a lung. It seems to take all the room. That’s because it’s full of air. However, while it touches the inside of the chest wall it’s not attached. The lung is quite pliable, of the consistency of a soft sponge, and is collapsible. Fluid accumulating in the chest outside the lung easily compresses it. This can happen when cancers spread to the pleura, the thin membrane that has two components. One covers the outside of the lung, the visceral pleura, and the other lines the inside of the chest, the parietal pleura.

The parietal pleura continually secretes fluid which lubricates the pleural surfaces to diminish friction as the chest and lung move against each other with each breath. This fluid is eventually absorbed by lymphatics in the lung and the mediastinum. When cancer metastasizes to either pleura (any malignancy can do this, but breast and gastrointestinal cancers are particularly frequent offenders) it can irritate enough to increase fluid production and disrupt blood vessels so that bleeding occurs. In addition, metastases to the mediastinum can obstruct fluid absorption. All this culminates in fluid building up inside the chest but outside the lung which is squeezed down. A collapsed lung cannot function. This can cause significant respiratory distress.

Depending on patients’ symptoms, specific treatment of this malignant pleural effusion may be necessary. There are two options. A temporary argyle tube can be inserted into the chest through which is instilled an agent (there are several) to induce sufficient inflammation that the two pleural surfaces adhere so fluid cannot accumulate. This is pleurodesis. The second option is to place a permanent catheter which hangs outside the chest and when the patient is short of breath can be used at home to evacuate fluid. Neither intervention is consistently successful and both have pros and cons which should be discussed with the treating physicians.