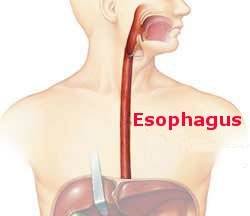

In 1895 William Macewen, a Scot, removed an entire lung from a patient with rampant infection. He was the first to successfully accomplish this operation, a pneumonectomy. Remarkably, he incorporated none of the technical actions that are and have been routinely and consistently used by thoracic surgeons for many years since it became a common operation for lung cancer. A thoracic surgeon accomplishes the following. The surgeon controls the blood vessels, the pulmonary artery full of blood moving from the heart to the lung and the two pulmonary veins returning the oxygenated blood to the heart, and the bronchus, the windpipe. These structures are controlled with either sutures or, more likely today in the era of minimally invasive surgery, with staples. The surgeon can then safely divide the blood vessels and bronchus, knowing that there will be no bleeding or air leakage because of this action.

Macewen did none of this. He encountered a lung consumed both by tuberculosis and bacterial infection. He more-or-less scooped the diseased lung out through a thoracotomy (an incision between the ribs). That’s it. No attempt to control blood vessels or the bronchus. And the patient survived. Amazing.

Why did this succeed. The hilum, the anatomic structures noted above, were undoubtedly buried in a mass of inflammatory tissue. Macewen couldn’t have even identified them much less sutured them. So, he did not define techniques for this operation for future use. He did accomplish something else of great importance called proof of concept. He established the feasibility of removing an entire lung and having the patient survive. Thoracic surgery was built on this building block.

As I have previously mentioned, Macewen impacted the evolution of surgery in the United States by turning down the offer to chair the Johns Hopkins department of surgery. William Halsted jumped into the breach and his many contributions to operative surgery and resident training followed.