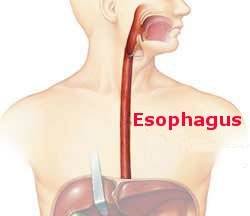

What is the goal of an esophagectomy?

The answer may seem obvious, but it was not always so. As recently as when I began my practice in the early 1980s the hoped-for outcome was that the patient’s dysphagia would be relieved. Cure of the cancer was a welcome result but was only obtained in 10% to 20% of the patients that survived the operation. So at that time the realistic goal was palliation.

The paradigm began to change as the 1980s progressed. My mentor, David Skinner, led the charge. Picking up a technique from a Scottish surgeon Logan, he developed an operation that differed from the current standard by removing a substantial envelope of tissue, including groups of lymph nodes, in continuity with the esophagus. This was an extensive procedure and the operative mortality was on the high side (around 10%) but there was a 25% survival rate. The most important finding was that for patients with only a few nodes harboring cancer survival was much better than obtained by others using the standard, less extensive, esophagectomy. The two important results were that the value of accurate staging (determining the extent the cancer had or had not spread) was emphasized and that the concept of cure had been introduced into the conversation.

Now an esophagectomy is only performed in the expectation of curing the cancer. Thorough staging before treatment is critical including the use of ultrasound with endoscopy to evaluate adjacent lymph nodes. Patients with metastases are not operated. All others, if healthy enough, receive chemotherapy and radiation and are restaged. An esophagectomy is performed if it appears all cancer, including involved lymph nodes, can be removed. With this multimodality program, experienced surgeons are reporting cure rates of 40% to 50% with operative mortality rates under 5%. We’ve come a long way.

My next blog will address palliation for those patients that are not candidates for an esophagectomy.