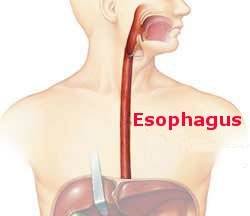

When I began my thoracic surgery practice in 1981 the prognosis for patients with esophageal cancer was worse than grim. It was a death sentence. The 10-year survival rate was close to zero. Happily, things have changed and outcomes are better. The SEER database now reports 10-year survival for new esophageal cancer patients is 20%. That’s a remarkable improvement. What happened?

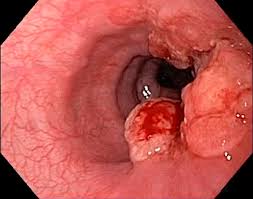

Let’s begin with the cancer itself. It’s a different cancer in two respects. Forty years ago the most common type was squamous cell carcinoma; it arose from the skin-like cells that line the inside of the esophagus, the mucosa. Adenocarcinomas are now by far more frequently encountered and squamous carcinomas are uncommon. These adenocarcinomas arise from the glands inside the wall of the esophagus or from the abnormal Barrett’s esophageal mucosa. The other change is the location of the tumor. In 1981 most esophageal cancers were in the middle of the esophagus, halfway between the mouth and the stomach. Now nearly all are in the lower part of the esophagus, near where it joins with the stomach. The change in cell type suggests a change in biologic behavior; current cancers may be more responsive to treatment. The change in location dictates different surgical tactics when an operation is performed. The different cell type and position in the esophagus must have impacted the improved response to our efforts to cure.

Simultaneously, treatments for esophageal cancer have evolved and improved. Thoracic surgeons have modified in several ways the operation they perform. Technical improvements have decreased the frequency of operative complications and more aggressive attempts to harvest lymph nodes is thought to have contributed to complete cancer eradication. Medical oncologic physicians have likewise developed more and more efficacious drugs than we had years ago. The current panoply includes chemotherapeutic drugs, immune modulators and drugs that interfere with cellular metabolic pathways. Radiation still plays an important role but is perhaps a little less effective for adenocarcinoma than squamous cell tumors. All these therapies alone or, with increasing frequency in combination, are responsible for the considerable improvement in prognosis.