There are few more distressing sensations than having difficulty swallowing, called dysphagia. There are, perhaps surprisingly, many causes of this feeling. The awareness of a lump in our throat when emotions run high—saying goodbye to a loved one for example—is, thankfully, short lived and only a temporary cause of difficulty swallowing. On the other hand, a cancer in the esophagus blocks the passage of food, starting slowly and then worsening, and if treatment is not forthcoming will completely obstruct. Any time someone notes and complains of having persistent trouble swallowing, because of the possibility of cancer it must be investigated.

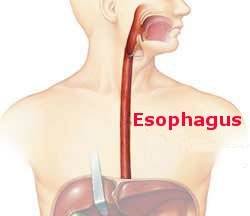

Sometimes this investigation will reveal the uncommon diagnosis of achalasia. This disorder, which usually presents in patient’s 20s, affects the muscles of the esophagus in two ways. The esophagus is a tubular organ that connects the mouth to the stomach. This biological conveyor belt transports food by literally squeezing it along with sequential muscular contractions, exactly as we extrude toothpaste. Achalasia disrupts this process by causing all the contractions to take place simultaneously; food is still squeezed but not propelled toward the stomach; stasis is the result. In addition, the muscular sphincter at the bottom of the esophagus, where it joins the stomach, fails to perform as it should. Normally the sphincter is constricted to prevent acid reflux but relaxes long enough to allow food to pass. With achalasia the sphincter fails to do so; this creates a muscular pressure at the bottom of the esophagus creating a second swallowing obstacle.

We do not know the cause of achalasia and medications do little to help. There are useful interventions and all are invasive. Surgery, performed laparoscopically (minimally invasively through small incisions), is used to cut the obstructing sphincter muscles, has a good track record, and is one I performed. A recently introduced method of cutting the muscle using an endoscope has the benefit of not requiring a skin incision and has reasonable early results but long-term outcomes are still uncertain.

More details about the diagnosis and treatment of achalasia, as well as other disorders of the esophagus and lungs, can be found in my book, “Cracking Chests: How Thoracic Surgery got from Rocks to Sticks.” Included is the tale of the treatment of the first person identified with achalasia who for years used a whale rib fitted out with a wad of cloths on its end to pass through his mouth, into his esophagus, and push its contents into his stomach.